The Importance of the Visual

The Lindisfarne Gospels, a 1,300-year-old manuscript, is revered to this day as the oldest surviving English version of the Gospels. Lindisfarne is a small island just off the Northumberland coast of England. It is often referred to as Holy Island. Tidal waters cut it off from the rest of the world for several hours every day, adding to its mystique as a spiritual pilgrimage.

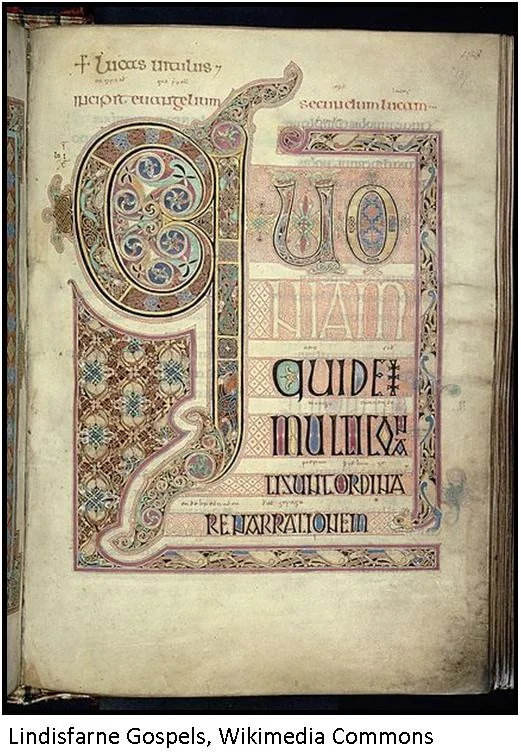

Produced around AD 715 in honor of St. Cuthbert, largely by a man named Eadfrith, the Bishop of Lindisfarne, the Lindisfarne Gospels presents a copy of the four Gospels of the New Testament. But it isn't revered simply for its age. Its pages reveal curvy, embellished letters, strange creatures, and spiraling symbols of exquisite precision and beauty. During the eighth century, pilgrims flocked to St. Cuthbert's shrine where it was housed, making the Lindisfarne manuscript one of the most visited and seen books of its day. Its artwork and symbols helped convey its message to those who could not read.

Professor Richard Gameson from Durham University sees it as a precursor to modern multimedia because it was designed to be a visual, sensual and artistic experience for its audience. Michelle Brown from the University of London notes that the book's impact was similar to those of films and electronic media today. As Gameson adds, "The emphasis was to reach as many people as possible."

There are many strategies needed for the church to have an open "front door" – to help those who were previously unchurched to come, and feel not only welcomed but to feel connected. In reaching the culture today it is clear that the church needs to be focused on a key element of this: be visual.

I have written in other places that there are striking parallels between our day and that of the Middle Ages. But if we are entering a new era that is similar to the earlier medieval era, what does that mean? If we are following the medieval pattern – and I believe that in many ways we are – there will be at least five dynamics:

widespread spiritual illiteracy

indiscriminate spiritual openness

deep need for visual communication

attraction to spiritual experience

widespread ethos of amorality

That is why the term neomedieval, first offered by Umberto Eco in regard to Western society, seems appropriate.

But it is the visual element that churches neglect to their peril. Over the last twenty years, we have decisively moved to a visually based world. The most formative influences are not books, theater, or even music.

They are films.

Throw in videos and the rise of YouTube, and you have the essence of a cultural revolution – not to mention something of a return to the medieval. For example, during the Middle Ages, there was widespread spiritual illiteracy, as well as actual illiteracy. People couldn't read. This is why pilgrimages mattered so much to the pilgrims. Beyond the relics and holy places they thought might bestow grace, usually the cathedrals they visited held relics that told the story of faith through a medium they could understand: stained glass, pictures.

So while people couldn't, or didn't, read, they couldn't help but see, and from seeing, understand.

It's no different today.

We are spiritually illiterate and are visually oriented and visually informed. Only now, instead of stained glass, we have film. At Mecklenburg Community Church, the church where I serve as senior pastor, there is very little we don't try to convey visually, whether it's a song during worship or a point during a message.

It's simply how people best receive information and meaning, content and context.

And because it part of the arts, it has a way of sneaking past the defenses of the heart.

James Emery White

Sources

Adapted from James Emery White, The Rise of the Nones: Understanding and Reaching the Religiously Unaffiliated (Baker). Click here to order this resource from Amazon.

Flavia Di Consiglio, "Lindisfarne Gospels: Why is this book so special?" BBC Religion and Ethics, March 20, 2013, read online.

Umberto Eco, Travels in Hyper Reality: Essays, trans. William Weaver (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1986), p. 73.